For physicians who are not familiar with the disease, ME/CFS is difficult to diagnose. For that reason, many patients with ME/CFS may be initially misdiagnosed with other illnesses. (The converse is also true. Many patients with other complex diseases in which fatigue is a predominant symptom have been misdiagnosed with CFS.) However, by following standard medical procedures – taking a careful history, ruling out similar illnesses, noting signs and symptoms typical of the disease, and ordering tests that are usually abnormal in ME/CFS patients – any physician can diagnose the disease.

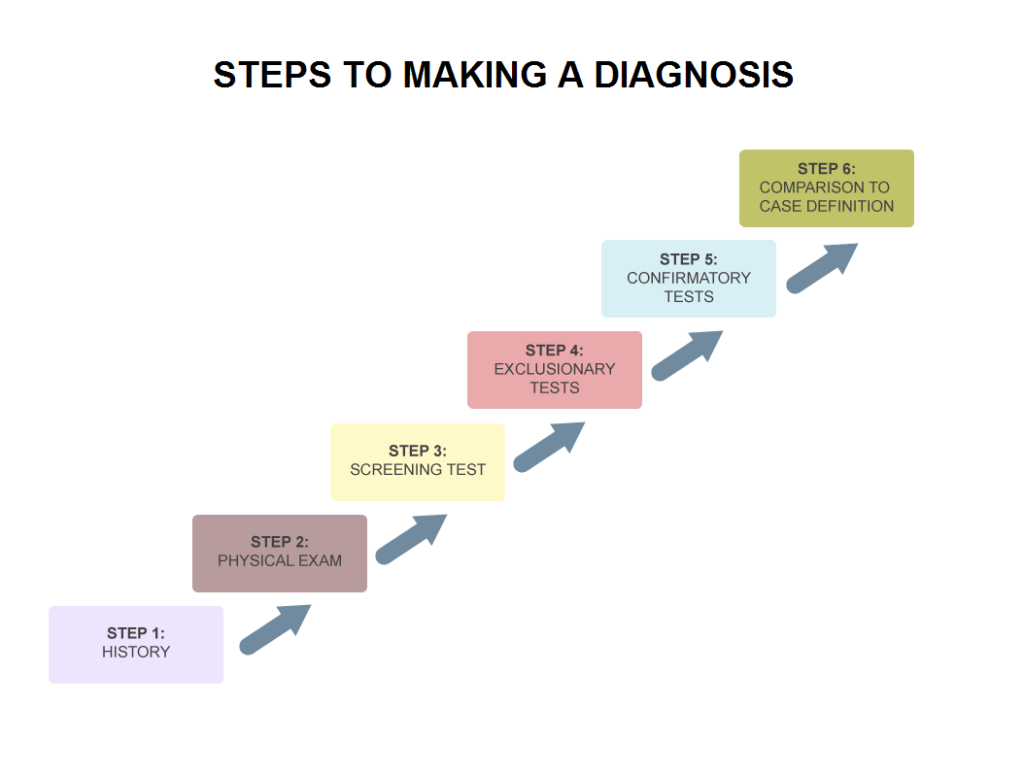

The first step toward making a diagnosis is taking a thorough history. Physicians should ask their patients when they first experienced symptoms, what events preceded the onset of symptoms, if other members of the family are also ill, other diagnoses and health problems, as well as any medications the patient is currently taking.

If your physician is experienced with ME/CFS, you may be asked to fill out a questionnaire, such as the DePaul Symptom Questionnaire, [http://www.iacfsme.org/Portals/0/pdf/kingquestionnaire.pdf ] prior to your visit, to help the physician assess the frequency and severity of your symptoms.

As part of the history, the physician should take into account the type of onset (acute or insidious), triggering mechanisms (exposure to chemicals, viral infection, physical trauma), and any other factors that might influence the severity or persistence of the illness. Symptoms that develop quickly after an initial trigger are highly suggestive of ME/CFS. In adolescents, the initial trigger is frequently mononucleosis.

Most specialists question their patients carefully about the range of symptoms they are experiencing. ME/CFS is a syndrome, which means that multiple symptoms are present. Many of these symptoms are reflective of an autonomic nervous system disorder; others are indicative of a persistent viral infection. What is important to the doctor is not necessarily that you have all of the symptoms, or even a certain percentage, but that they cover a spectrum. The symptoms most doctors consider as particularly significant are the persistent loss of energy not relieved by rest, a worsening of symptoms after mild exertion (post-exertional malaise), pain, sleep disorders, and cognitive problems. Other symptoms can occur in an astonishing array.

Even if the patient does not have all of the symptoms, it is unlikely that a doctor will make diagnosis based strictly on fatigue. Fatigue is one of the primary symptoms of all autoimmune diseases as well as major depression. However, unlike patients with ME/CFS, those with depression feel better after exercise. Any doctor familiar with ME/CFS will ask the question, “How do you feel after you exercise?” (A patient with ME/CFS will reply, “Awful!”)

Conscientious physicians should order all the necessary tests to rule out illnesses that produce similar symptoms, particularly fatigue. A significant percentage of patients who have rare or hard-to-detect diseases, such as Behçet’s Disease, rare forms of leukemia, early MS, Lyme disease, and empty sella (shrunken pituitary) have been erroneously diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome, because they initially presented with fatigue. To avoid a misdiagnosis, it is important for patients to mention symptoms other than fatigue in the initial consult.

Once the physician has taken a thorough history and assessed symptoms and ruled out other diseases, he or she should then compare the symptoms to a case definition.

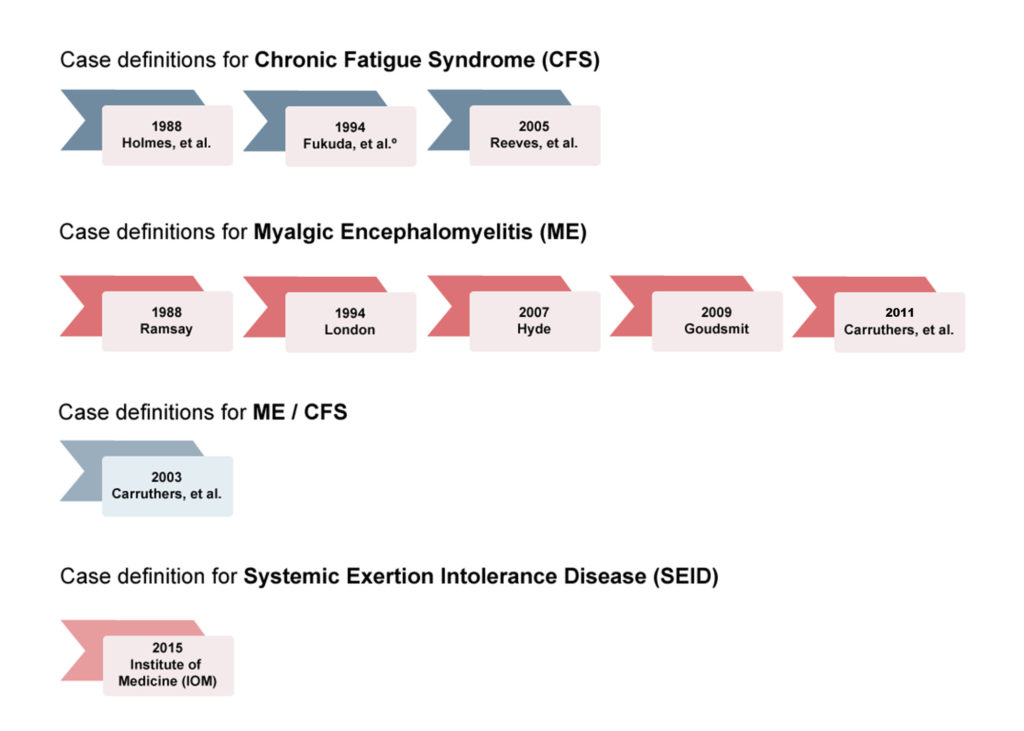

Comparison to a case definition can be problematic, as many have been developed over the years, and few have sufficient specificity and sensitivity to be useful. Physicians who are not ME/CFS specialists generally rely on the 1994 CDC case definition (also known as the Fukuda definition) to make a diagnosis. Because the Fukuda definition is very broad, it often leads to misdiagnoses (De Becker et al, Jason et al.). As a consequence, ME/CFS specialists prefer to use the more accurate Canadian Consensus Criteria (CCC), or the International Consensus Criteria (ICC). The most recent case definition is the 2015 Institute of Medicine for Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease. It has not been officially adopted, but several preliminary studies performed by Leonard Jason’s group at De Paul University indicate that it captures a substantial number of people who do not have ME/CFS, but have major depression, lupus, and MS. As a consequence, there is some doubt as to its utility.

Of all the case definitions developed over the last three decades, the least reliable is 1991 Oxford case definition. It is a broad definition, requiring only six months of mental or physical fatigue as well as optional symptoms common to psychiatric diagnoses. Due to its lack of specificity, the 2014 Pathways to Prevention Workshop recommended that the Oxford case definition be retired.

SIGNS AND OFFICE OBSERVATIONS

A physical exam is an important part of making a diagnosis. While ME/CFS is often called an “invisible illness,” there are some distinctive features that are apparent during a routine examination:

- Blood pressure: usually low (orthostatic hypotension)

- Temperature: low (97° F) or slightly elevated (<100° F) or, more commonly, both over the course of a day (excessive diurnal variation)

- Heartbeat: tachycardia (hard to detect in an office visit; Holter monitor is more efficient)

- Throat: irritated, crimson crescents

- Lymph nodes: tenderness in nodes of groin and neck, particularly on left side

- Pallor: Dr. Cheney noted a “ghastly pallor” in his Caucasian patients

- Positive Romberg test (tandem stance)

- Stiff, slow gait

- Nystagmus (involuntary eye movements)

- Photophobia (light sensitivity)

- Hyperreflexia (increased reflex reactions)

Common Findings on Routine Screening Tests

Physicians usually order routine screening tests, such as a complete blood count (CBC) with differential, a urinalysis, and liver function tests, as part of their initial examination. While these tests are useful to eliminate other possible diagnoses, there are also a few abnormalities that are typical of people with ME/CFS.

- Decreased number of white blood cells (leukopenia), also increased number of white blood cells

- Abnormal red blood cell membranes, elevated MCV (large red blood cells)

- Low concentrations of zinc and magnesium

- Low uric acid concentration (<3.5 mg/dl)

- Total cholesterol concentration slightly elevated

- Decreased potassium and sodium

- Sedimentation rate: Low (<5 mm/hr); sometimes brief periods of elevated rate (>20 mm/hr)

- Urinalysis: alkaline; mucus or blood, or both, without bacterial infection

- Positive ANA, speckled pattern

- Liver function tests: mildly elevated AST (SGOT) and ALT (SGPT)

WHAT TESTS ARE RECOMMENDED FOR ME/CFS?

When a patient presents with debilitating fatigue as a primary symptom, physicians must perform a battery of tests to rule out other illnesses that produce chronic fatigue, including leukemia, MS, kidney disease, brain injury, liver disease, thyroid disease, infections such as Lyme, and autoimmune diseases.

In most instances, exclusionary tests are not expensive or difficult to perform. Depending on the symptoms, the physician may wish to rule out ongoing Lyme disease, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis or other autoimmune disorders, parasitic infections, heart disease, specific neurological disorders such as multiple sclerosis, endocrine disorders such as hypothyroidism, and systemic infections and inflammatory conditions (as indicated by a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate).

In general, patients with ME/CFS test negative for other conditions. However, as many physicians have noted, nothing prevents a person from having two conditions simultaneously or developing one after the other. Thus a positive test result does not necessarily rule out a diagnosis of ME/CFS.

Exclusionary Tests

| Autoimmunity >>> | Negative for lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Hashimoto’s disease. Note: Patients sometimes test positive on initial screening but not on more specific tests.

|

| Endocrine system >>> | Negative for Addison’s disease, Cushing’s disease, hypothyroidism, diabetes mellitus. Note: Although some patients with ME/CFS with enlarged thyroid gland test negative on standard tests, more refined tests may reveal secondary thyroid deficiencies. Many patients also develop co-morbidities such as Hashimoto’s disease and diabetes.

|

| Heart >>> | Negative for mitral valve prolapse. Note: Test is warranted if the patient reports tachycardia. Tests sometimes reveal elevated transaminase concentrations and angiotensin-converting enzyme.

|

| Liver >>> | Negative for hepatitis.

|

| Nervous system >>> | Negative for multiple sclerosis (MS). Note: Test is warranted if patient shows severe neurological, cognitive, and muscle dysfunction. Although some patients with ME/CFS may test negative for MS, more specific testing (brain function) may reveal abnormalities.

|

| Bacterial >>> | Negative for tuberculosis, brucellosis, *Lyme disease.

*Note: Current Lyme tests are notoriously unreliable. Doctors should order repeated tests for patients in Lyme endemic areas to rule out tick-borne diseases, as the symptoms of ME/CFS and Lyme disease are virtually identical.

|

| Cancer >>> | Negative for lymphoma and leukemia.

|

| Parasites >>> | Negative for toxoplasmosis, giardiasis, amoebiasis. Note: Patients with ME/CFS can have multiple parasitic infections as part of a prodromal illness. (An illness that immediately precedes ME/CFS.)

|

Confirmatory Tests

Even though there is no single test that is universally accepted as a biomarker, there are some tests that are consistent with a positive diagnosis of ME/CFS. These tests are usually expensive, specialized, and, in most cases, cannot be performed locally. A diagnosis can be made without performing any of these tests, but if they are available, a positive result on two or more of these tests (especially exercise testing) would be strongly indicative of ME/CFS. Not all of these specialized tests are necessary to make a diagnosis, although someone applying for disability insurance may need some of them to file.

| 2-Day CPET | Decreased cortisol levels after exercise, decreased cerebral blood flow after exercise, inefficient glucose utilization, erratic breathing pattern. In Cardio-Pulmonary Exercise Testing with measurement of VO2 max, patients with ME/CFS score significantly lower than controls.

|

| Viral reactivation | Positive for cytomegalovirus, Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6 and 7, and Coxsackie virus; negative for hepatitis A or B virus.

|

| Immune system | Low natural killer cell counts, elevated interferon alpha, tumor necrosis factor, interleukins 1 and 2; T cell activation, altered T4/T8 cell ratios, low T cell suppressor-cell (T8) count, fluctuating low and high T cell counts, low and high B cell counts, antinuclear antibodies, immunoglobin deficiency, sometimes antithyroid antibodies.

|

| SPECT brain scan | Hypoperfusion in either right or left temporal lobe, particularly Wernicke’s area, after exercise.

|

| MRI brain scans | Unexplained bright areas.

|

| Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

(MRS) brain scan |

Abnormally high lactic acid spikes near around the hippocampus, which indicates mitochondrial dysfunction.

|

| Heart function | Abnormal impedance cardiography; repetitively oscillating T wave inversions and/or T wave flats during 24-hour Holter monitoring.

|

For those who can afford it, a single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scan can reveal areas of the brain with reduced blood flow, a common finding in people with ME/CFS. MRIs of the brain often show small plaques, an indication of brain injury. For patients with severe cognitive impairment, IQ tests and other neurocognitive examinations may be recommended.

Immune system tests can be used to confirm a diagnosis of ME/CFS. Immune system testing is specialized, so results cannot be reliably interpreted by anyone other than an immunologist or ME/CFS physician. Even among specialists, there is tremendous dissent as to what these test results actually mean. The value of having these tests done is to determine whether the patterns seen in the test results are similar to those of other people with ME/CFS. Many (but not all) people with ME/CFS have reduced numbers of natural killer cells and increased numbers of circulating cytokines (such as alpha interferon and the interleukins). Immune cell function also may be measured. Patients with ME/CFS generally have diminished NK cell, T and B cell function. (Brenu et al.) Reaction to pokeweed mitogen, total immunoglobulin production (IgG, IgA, IgM), and demonstrable anergy (lack of immune response) when tested with foreign proteins can help determine immune cell responsiveness.

Along with immune system tests, most ME/CFS specialists look for evidence of viral reactivation. People with ME/CFS usually show evidence of reactivation of latent viruses, particularly in the herpesvirus family, such as Epstein-Barr virus, human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6), and cytomegalovirus. Enteroviruses may also be present. Reactivation of latent viruses (as indicated by high titers) provides further proof of immune system dysfunction, because in a healthy person these viruses are controlled.

Research has shown that people with ME/CFS have inflammation in the brain, as well as a specific cytokine (immune system chemical) signature (Yasuhito Nakatomi et al., Brenu et al.). There are also distinct changes in spinal fluid proteins (Schutzer et al.) A Columbia research team led by Dr. Mady Hornig has even found distinct changes in cytokines between recently ill patients compared to long-term patients. While most medical practitioners cannot order tests to confirm these findings, they may eventually lead to a biomarker – a single test to confirm a diagnosis.

REFERENCES

Allen J, Murray A, Di Maria C, Newton JL. “Chronic fatigue syndrome and impaired peripheral pulse characteristics on orthostasis-a new potential diagnostic biomarker.” Physiol Meas. 2012 Jan 25;33(2):231-241 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22273713

Brenu, Ekua W, Mieke L van Driel, Don R Staines, Kevin J Ashton, Sandra B Ramos, James Keane, Nancy G Klimas, and Sonya M Marshall-Gradisnik. “Immunological abnormalities as potential biomarkers in Chronic Fatigue Syndrome/Myalgic Encephalomyelitis.” Journal of Translational Medicine 2011, 9:81. http://www.translational-medicine.com/content/9/1/81

Carruthers, Bruce M. and Marjorie I. van de Sand. “Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/ Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Clinical Case Definition and Guidelines for Medical Practitioners An Overview of the Canadian Consensus Document.” https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21777306

Carruthers, BM, M. I. van de Sande, K. L. De Meirleir, N. G. Klimas, G. Broderick, T. Mitchell, D. Staines, A. C. P. Powles, N. Speight, R. Vallings, L. Bateman, B. Baumgarten-Austrheim, D. S. Bell, N. Carlo-Stella, A. Darragh, D. Jo, D. Lewis, A. R. Light, S. Marshall-Gradisbik, I. Mena, J. A. Mikovits, K. Miwa, M. Murovska, M. L. Pall, S. Stevens. “Myalgic encephalomyelitis: International Consensus Criteria.” Journal of Internal Medicine. Vol. 270 Issue 4, pages 327–338, October 2011. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/j.1365-2796.2011.02428.x/full

De Becker P, McGregor N, De Meirleir K. “A definition-based analysis of symptoms in a large cohort of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.” J Intern Med. 2001 Sep;250(3):234-40. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11555128

Fukuda, Keiji MD, MPH; Stephen E. Straus, MD; Ian Hickie, MD, F RANZ C P; Michael C. Sharpe, MRCP, MRC Psych; James G. Dobbins, PhD; Anthony Komaroff, MD; and the International Chronic Fatigue Syndrome Study Group. “The Chronic Fatigue Syndrome: A Comprehensive Approach to Its Definition and Study.” Ann Intern Med. 1994;121:953-959. http://www.ncf-net.org/patents/pdf/Fukuda_Definition.pdf

Hornig, Mady, José G. Montoya, Nancy G. Klimas, Susan Levine, Donna Felsenstein, Lucinda Bateman, Daniel L. Peterson8, C. Gunnar Gottschalk8, Andrew F. Schultz1, Xiaoyu Che1, Meredith L. Eddy1, Anthony L. Komaroff9 and W. Ian Lipkin. Distinct plasma immune signatures in ME/CFS are present early in the course of illness. Diagnostics 2015, 5(2), 272-286; doi:10.3390/diagnostics5020272 http://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/5/2/272

Jason, Leonard A. Beth Skendrovic, Jacob Furst, Abigail Brown, Christine Bronikowski, Angela Weng. “Data mining: comparing the empiric CFS to the Canadian ME/CFS case definition.” Journal of Clinical Psychology. Volume 68 Issue 1, pages 41–49, January 2012 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3228898/

Leonard A. Jason , Madison Sunnquist, Bobby Kot, and Abigail Brown. Unintended Consequences of not Specifying Exclusionary Illnesses for Systemic Exertion Intolerance Disease. Diagnostics 2015, 5, 272-286; doi:10.3390/diagnostics5020272 http://www.mdpi.com/2075-4418/5/2/272

US ME/CFS Clinician Coalition Recommendations for ME/CFS Testing and Treatment, April 13, 2021. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1Yu79EYxQIwNVER5tErp7LH7KY8pI8S_e/view

Schutzer, Steven E., Thomas E. Angel, Tao Liu, Athena A. Schepmoes, Therese R. Clauss, Joshua N. Adkins, David G. Camp II, Bart K. Holland, Jonas Bergquist, Patricia K. Coyle, Richard D. Smith, Brian A. Fallon, Benjamin H. Natelson. “Distinct Cerebrospinal Fluid Proteomes Differentiate Post-Treatment Lyme Disease from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome.” PLoS ONE 6(2): e17287. (2011) http://www.plosone.org/article/info:doi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0017287

U.S. ME/CFS Clinician Coalition. Diagnosing and Treating MYALGIC ENCEPHALOMYELITIS/CHRONIC FATIGUE SYNDROME (ME/CFS). August 2019. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1SG7hlJTCSDrDHqvioPMq-cX-rgRKXjfk/view

Yasuhito Nakatomi, Kei Mizuno, Akira Ishii, Yasuhiro Wada, Masaaki Tanaka, Shusaku Tazawa, Kayo Onoe, Sanae Fukuda, Joji Kawabe, Kazuhiro Takahashi, Yosky Kataoka, Susumu Shiomi, Kouzi Yamaguti, Masaaki Inaba, Hirohiko Kuratsune, Yasuyoshi Watanabe, “Neuroinflammation in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome/myalgic encephalomyelitis: a 11C-(R)-PK11195 positron emission tomography study”, The Journal of Nuclear Medicine, vol.55, No.6, 2014, DOI: 10.2967/jnumed.113.131045 http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/early/2014/03/21/jnumed.113.131045

Further diagnostic tools for orthostatic intolerance: